Pricing – Keep it Simple, Fair While Maximizing CLV

In this article Mark Stiving teaches how simple pricing is better, how to price to maximize the Customer Lifetime Value, which refers to how much value (or revenue) we could earn from a customer over their time with us as a customer.

1. Sell More by Keeping Prices Simple

Humans are interesting creatures. We can understand and implement concepts of such complexity – and yet, we are allured by simple things. When it comes to economic decisions (like what we buy), the easier the decision is, the more likely we are to make a commitment. Just as behavioral economist Richard Thaler said:

“If you want someone to do something, make it easy”

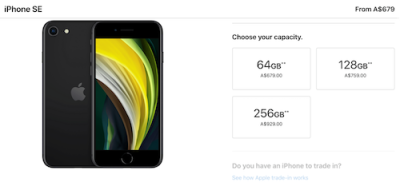

Now, presenting simple prices, and using price segmentation and other techniques, are not mutually exclusive. You absolutely should think deeply about your pricing. Your pricing could even be fairly complex in the back-end, but simple and easy for customers to understand in the front-end — this is how LinkedIn does it. Apple is another example of simple pricing: easy to understand, but still well-thought out by their pricing people:

When customers see simple pricing, they are more likely to make a decision (resulting in a sale), because there is less friction – there is less complexity their brain has to work through to decide what they want. Conversely, when they see complex pricing, they are less likely to make a decision – hence, no sale.

Think about shopping for something on Amazon’s website. What you see is the item and its price. Very simple. What you don’t see is that Amazon has complex algorithms that look at their customer’s purchase history, zip code, maybe even the credit limit on their credit card – to determine what price to charge each customer. But in the end, Amazon shows only one price to their customer. Complex pricing, simple price presentation.

The lesson we should learn is to ensure that while we think deeply and strategically about our pricing, that we keep its presentation simple for our customers. It’s a more positive experience for them, and a more profitable outcome for us.

2. Three Rules to Keep Your Pricing Fair

To maximize the profit increase you can achieve through pricing, you must use some form of price segmentation. After all, not all customers have the same willingness to pay. Setting different prices for the same product/service means more people can buy from you, and you earn more revenue.

But is price segmentation fair?

Is it fair if we charge some people one price, and other people a different price? Think about your own experience: how do you feel when you pay one price, only to find out someone else bought it cheaper?

LOOKING THROUGH A CLOSER LENS AT “FAIRNESS” WHEN PRICE SEGMENTING

As it turns out, fair is in the mind of the beholder.

Each individual determines whether or not he or she has been treated fairly, since every person has their own sense of what ‘fair’ is. Now, there are some examples where it appears there is general consensus on what is and isn’t fair. Let’s have a look at some examples:

- Students getting into movie theaters at a lower price. – Fair

- Seniors getting cheaper coffee at McDonald’s. – Fair

- Vacation travelers paying less for flights than businessmen. – Fair

- Paying more for Coke on hot days than on old cold days. – Unfair

- Paying more to check your bags on an airline. – Unfair

As we think about these and other examples, there seem to be three criteria which makes something “fair.”

THREE FAIRNESS RULES IN PRICING

- The different price is a discount to one group, not a surcharge to the other group.

- The pricing rules are transparent to the customers, and the customers have learned to play by them as they become more ‘normal’.

- The rules do not change. And if they do change, they change in the customers’ favor.

I’m personally still amazed when people are upset when the airlines charge more to check-in a bag, but they don’t complain when they have to pay for a meal. While it is to your benefit to segment your customers – and charge different prices – you should pay attention to the three rules above if you want to avoid creating a negative experience for your customers.

3. Pricing for Customer Lifetime Value

Customer lifetime value refers to how much value (or revenue) we could earn from a customer over the duration of their time with us as a customer. So long as it’s profitable to do so, a business should prioritize deepening and lengthening this metric. So, how do you price to maximize the lifetime value of a customer? It’s an interesting question. In its simplest form, the issue comes down to customer capture and customer retention.

CUSTOMER CAPTURE AND RETENTION FOR MAXIMUM LIFETIME VALUE

What does it take to capture a new customer? Of course, when we price a product we aren’t guaranteed to always make the sale. In general, the lower we price a product, the higher the probability the customer will buy it. If it is a one-time purchase (meaning selling this one doesn’t make it more likely to sell the next one to the same customer), then we would simply choose the profit maximizing price.

However, if we believe that capturing a customer makes it more likely to sell another product later, to the same customer, then it may be in our benefit to lower our price so we can win more customers up front. We often see special rates to new subscribers for satellite TV services, or cell phone services. Within these industries, they can determine if you are a new customer or not. And once they have you, they really lock you in (for years). As well as low prices, we also see products sometimes offered for free in order to capture new customers. For example, free samples of products or free trial periods of software. The more likely you are to sell another unit to the same customer (if you’ve already sold them one), the lower you can set your customer capture price.

Other customer retention prices work the same way, only they are slightly higher. Companies who price this way recognize they have some “loyalty”, meaning the customer is predisposed to purchase their product over their competitors. This way, a company can charge a higher price than they would if the customer were making a first-time decision. After all, you should be able to capture customers’ loyalty. When you set a customer retention price, some customers will buy and some won’t. You may be tempted to select the profit maximizing price for this decision.

But note that you are in a similar position as you were when setting the customer capture price. If you win a customer, you may have a higher probability of winning them again. This gives you extra incentive to lose fewer customers, motivating you to price lower than your profit maximizing price. This price of course is going to be higher than the customer capture price, but not as high as it would be if you knew this is the last this customer will purchase from you (or give you loyalty).

WHAT IF YOU COULD SEGMENT LOYAL CUSTOMERS FROM THOSE THAT MAKE STAND-ALONE DECISIONS EVERY TIME?

The above logic implies you may want to give your loyal customers lower prices, because this can keep them coming back. Restaurants like Subway offer a ‘buy 10 get 1 free’ card to do exactly that. They offer their loyal customers a 10% discount (actually 9% – but who’s counting?) while the non-loyal customers pay full price.

The real answer though is, it depends. It’s quite possible the loyalty is so high that you may be able to charge an exorbitant price to most of your repeat customers, while losing only a few. In this case, you would charge them more than a non-loyal customer if possible. Yet I can only think of three scenarios where you could get away with this:

- The customer is ignorant of other prices, and just continues writing the check.

- The customer is somehow locked into the deal, like a cell phone contract.

- The customer faces high switching costs (similar to 2), presenting resistance to changing products.

In the absence of one of those three conditions, you should set your loyal customer price lower than (or equal to) your non-loyal customer price.

Summary – Without going through any complex math, our observations tell us two things: first, charge a lower capture price for customers who are likely to make a repeat purchase; and second, for repeat purchases, charge more than the capture price, but less than what you’d charge a non-loyal customer.

Identify your path to CFO success by taking our CFO Readiness Assessmentᵀᴹ.

Become a Member today and get 30% off on-demand courses and tools!

For the most up to date and relevant accounting, finance, treasury and leadership headlines all in one place subscribe to The Balanced Digest.

Follow us on Linkedin!