Accounting and Finance for Non Accounting and Finance Managers

The following transcript is from a short video we created on general accounting concepts that was specifically designed for non accounting and finance professionals. Share this transcript and the video that goes with it with your non accounting/finance staff to help grow their financial acumen. View the video here: Accounting and Finance for Non Accounting and Finance Professionals

Enjoy the transcript below.

Hi, it’s Steve from CFO.University. Welcome to our brief course ‘Accounting and Finance for non Accounting and Finance Professionals’. Our goal today is to teach you some key points about these professions. With finance being the universal language of business, we believe this is a great professional growth opportunity for you. Enjoy the learning filled journey you are about to embark on.

Here is what you can expect from our brief adventure today. We are calling it Accounting 101. We will go through the history of the profession and explore whether the profession is a science or an art. You’ll learn about some of the top secrets of Accounting and Finance. Secrets you will not want to miss. We’ll briefly discuss the Accounting reporting triad of the balance sheet, the income statement and the cash flow statement. Finally, we’ll work through an example that will drive these concepts home for you.

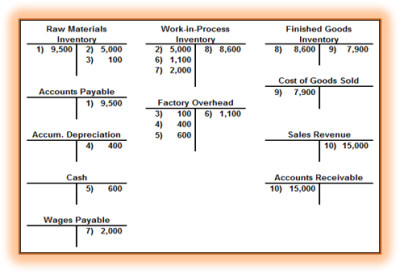

A little history first. To the left is an image of Luca Pacioli, a Franciscan Monk from Sansepolcro Italy, who lived in the 15th century. Friar Pacioli is known as the father of accounting. He invented double entry bookkeeping and the T account, the tool most often used and cursed by first year accounting students. The left side of the T account is where debits are recorded and the right-hand side is where credits are recorded. Below is an

example of a T account at work. The number to enter on each account has a corresponding entry on the opposite side of the T in a different account. For example, in the upper left corner, you can see raw materials inventory with a $9500 next to it. That entry is recording that we bought some raw materials and there is an offset entry right below it in accounts payable because we owe somebody for the inventory that we bought. Every entry in accounting has to have equal sides. One a debit, the other a credit. Is accounting, a science or is it an art? It’s an age-old question for the industry. If we assume accounting as a science, can you guess what is the accounting equivalent of Einstein’s theory of relativity? It is the accounting principle that assets always equal liabilities plus owner’s equity. This equation represents what is referred to as the balance sheet, one of the reports in the accounting triad.. Here is another good science analogy. Think of Friar Pacioli’s double entry bookkeeping system as the equivalent of Newton’s third law of physics rewritten as for every entry, there’s an Opposite and equal reentry, or debits must equal credits.

So now after the science, we have a double entry rule, Newton’s equivalent of the third law of physics and balance sheet must balance rule, Einstein’s theory of relativity. What else is there?

This is where we get into the top-secret part. Everything else is art! This isn’t meant to give you a new appreciation for the accountants in your company, but it is meant to make you aware that although accounting may appear prescribed, it is actually quite flexible. This is where the art in accounting comes in. There is art in determining when activity should be recognized or booked and in making estimates for the amount to be booked. Let’s go through some examples of major accounts on the balance sheet in the income statement. This might give you a better idea what I’m talking about

When do we book amounts due from customers or receivables?

Receivables could be booked when a contract is signed, when an order is made, when a product ships, when a product is made or when title transfers. There are all kinds of options as to when we could record and when we shouldn’t record receivables.

Amounts due vendors or accounts payable are the flip side of accounts receivable with similar issues.

How should we handle these items related to inventory? Should inventory be recorded when ordered, when received, when title transfers or when paid for? When should we write off inventory for being obsolete or unsalable? What if inventory is difficult to count, how do we estimate what goes into our products and how much is left at period end?

What about handling fixed assets. Fixe assets are normally recorded at what we pay for them (“historical cost”) and they sit on the balance sheet for a long time. Typically they decline in value from use and time. This is called depreciation. Depreciation is an estimate that includes the dimensions of time and utility. We must predict the assets useful life and rate of decline when it’s put on the books. Is the seer a scientist or an artist?

If we run over to the income statement, you might think okay, what about revenues – where is the art in recording them? Well, ask yourself, when should a sale be recognized? We could record it when the order is made, when it’s delivered, when it’s paid for. How should the sale be recorded if there’s a warranty on the product or some other future liability attached to it.

What about salaries, benefits and vacation accruals? We could record them when paid or when earned. How much of our personnel costs belong in inventory and how much is administrative? Does it make a difference?

Do you wonder why I’m making a big deal out of this? The big deal is that financial statements are important. They are relied on by investors, by bankers, by stakeholders and by employees. Understanding how art and science apply to these financial statements is really important. Understanding some of the nuances on where the art comes in, helps you ask the right questions.

Now that you learned how your accountants are like artists and how important the financial statements are, let’s travel through the financial statements and learn a little bit more about them. There are three main accounting statements.

The balance sheet or statement of financial position measures what we own, what we owe and what is the left-over (equity) at a specific point in time.

The income statement, statement of financial operations, the earnings or profit and loss report measures revenues and expenses over a period of time to determine financial performance. The cash flow statement highlights how cash was generated and consumed over a period of time using three major buckets operations, investment/divestitures and financing.

The first report we’ll talk about is the balance sheet or statement of financial position. Remember, there is science in our profession that applies specifically to the balance sheet. It must balance! Assets always equal Liabilities plus Equity. It is a measure at a point in time (not over a period of time). What it covers includes:

- What you own or your asset base

- What you owe, your liabilities.

- The difference of those two is what’s left over or the equity in the business. That’s what the shareholders, partners and owners own.

Here are a couple examples of where the balance sheet falls short an capturing the true economics of the business. Assets on the balance sheet don’t include the value of our human resources and some intangible assets. Most assets are recorded at historical cost with two major exceptions. Assets may be written down if there is support they are “impaired”. In markets with very transparent pricing, mark to market valuations may be used. In these cases current market values are used to value inventory on the company’s balance sheet. Even in a marked to market scenario it’s important to understand that a balance sheet almost never reflects the market value of the company. That’s an important concept to understand when you’re looking at and talking about the balance sheet. This is one area where some understanding of the financial statements can help you ask the right questions to learn more about the difference between the book value and market value of a company.

The next report we’ll talk about is the income statement. Also known as the statement of financial operations, the earnings report and the p&l (the profit loss report). There are two main components when it comes to the income statement. There is the revenues/sales components and there are the expenses. Those two components make up the profits or earnings of the business. Revenues are what we sell. They can be products or services. Expenses are what we consume to create what we’re selling and earning revenue from. The result of those two is our operational performance. Earnings measure how well our business plan is working over a period of time.

There are two key principles in the income statement. The first one is matching the timing of revenue and expenses. An important part of the artistry your accountants perform to make sure that the financial statements and particularly the income statement are worthwhile. This helps us analyze and create transparency into the business when done well. We want to make sure that expenses that relate to specific products, the timing of the revenues and when the expenses are recognized are recorded properly. A related concept is period versus product costs. Period expenses are expenses we can’t allocate directly to products. These normally get expensed as incurred. Product costs can be attributed to specific products so they get capitalized (added to inventory) until the product is sold and are expensed when the sale is recognized – whence the term matching revenues with expenses. The idea is to link specific expenses to specific sales revenue streams to help us analyze the business. When that isn’t possible the cost ends up as overhead or period cost. Your accountants spend a lot time getting these pieces right to improve the financial transparency of your business, making financial analysis that much better.

The third report of the accounting triad is the often overlooked but very important cash flow statement. The cash flow statement shows what aspects of the Business are generating and using cash. It’s a period report. What it covers it measures over a period of time, like the income statement. To the right is an example cash flow statement. It’s a cash reconciliation that highlights how cash was generated or consumed in the three key activities of any business:

- Operations

- Investment

- Financing

The “scientific” principle in this report is the cash balances at the beginning and end of the period must be same as the cash balances on the corresponding balance sheet.

Here is another way to view cash flow statement. Start with your beginning cash balance, add what’s collected (inflows), from each of the three activities; operations, investment or financing. Then subtract what’s been paid (outflow) from these same activities. The result is your ending cash balance.

Both the cash flow statement and income statement are period (not point in time) measures but a key difference is the cash flow statement identifies where the cash came and went where the income statement measures operating performance during the period measured. A company operating poorly, evening one reporting a loss could show positive cash flow from such things as selling long term assets or raising capital through financing. As a matter of fact both of these strategies are frequently used to raise cash in companies that have hit a rough patch operationally.

Another significant difference between most cash flow statements and income statements is the concept of accrual accounting. The income statement uses accrual accounting to match revenues and expenses to provide a more accurate picture of operational performance. The cash flow statement’s main focus – just as the name implies – is cash. The matching principle is disregarded to only focus on transactions that generate or consume cash.

A goal of most companies is to generate cash that can be invested in wildly fantastic investment opportunities. To that end, the cash flow statement helps us break down where we’re generating and where we’re consuming cash.

Well, that concludes the instructional part of Accounting and Finance for Non Accounting and Finance Managers. This won’t qualify you for a Chartered Accountant or Certify you as Public Accountant but it will help you ask the right questions the next time your accounting team presents with a set of financials.

For an exercise to hone your new found accounting skills go to our case study and apply them to our example, called Pat’s Pastries.

Identify your path to CFO success by taking our CFO Readiness Assessmentᵀᴹ.

Become a Member today and get 30% off on-demand courses and tools!

For the most up to date and relevant accounting, finance, treasury and leadership headlines all in one place subscribe to The Balanced Digest.

Follow us on Linkedin!